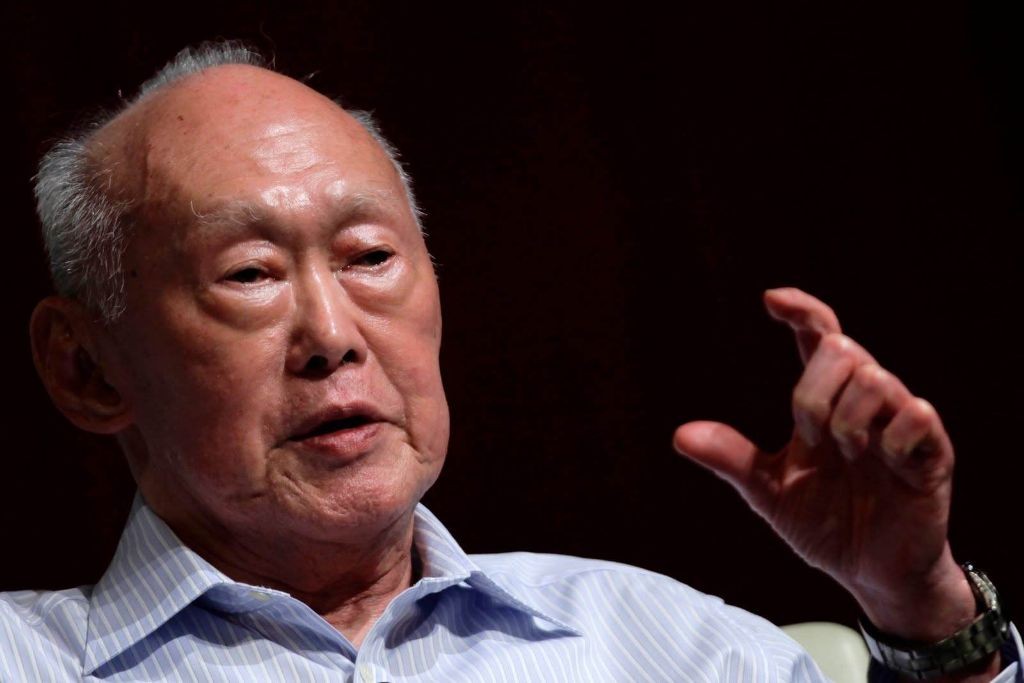

Singapore – Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of modern-day Singapore, has died. He was 91. The former prime minister, who had been hospitalised in intensive care for severe pneumonia since early Feburary, died early on Monday morning in Singapore General Hospital.

Incumbent Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s office announced seven days of mourning in the city-state ahead of a state funeral next Sunday.

Lee is widely considered to be single-handedly responsible for Singapore’s unique success story, the architect behind its fantastic transformation from glorified fishing village into one of the world’s economic powerhouses.

Singaporeans and world leaders paid tribute on Monday to a man described by US President Barack Obama as a “true giant of history”.

A complex and controversial figure, Lee’s adherence to the rule of law and tight social control ushered in an era of peace and prosperity that he worried in his later years would be taken for granted by a younger generation of Singaporeans.

Showing the physical frailty that comes with his 91 years, Lee made relatively few public appearances in recent years. But by many accounts, Singapore’s first and longest-serving prime minister remained mentally active, continuing to write occasional books and opinion columns, and sometimes stepping into policy debates about the island-nation’s future.

With Singapore nearing its 50-year-old mark as a nation in August 2015, Singaporeans wonder aloud what their country will look like without its founding father.

“Mr Lee’s biggest legacy to Singapore is to have Singapore continue robustly as a unique state even after his passing,” Eugene Tan, an associate professor of law at Singapore Management University, told Al Jazeera.

“A Singapore that cannot endure and thrive beyond Mr Lee would be an indictment of Mr Lee’s leadership and legacy.”

Rough start

Born Harry Lee Kuan Yew on September 16, 1923, a British subject in colonial Singapore – he omitted his English name Harry after reading law at Cambridge University.

Lee saw his country survive a brutal three-year Japanese occupation during World War II, and a short-lived merger with Malaysia that brought an end to British colonial rule.

He became Singapore’s first prime minister in 1959 when it became a self-governing state within the Commonwealth, and continued in the post from the country’s independence in 1965 until he stepped down in 1990. He went on to assume successive ministerial positions.

“The Father of Singapore” as he came to be known, first took power amid a host of problems including a multi-racial and multi-religious society with a history of violent outbursts, inadequate housing, unemployment, a lack of natural resources such as a water supply, and a limited ability to defend itself from potentially hostile neighbours.

Whip-smart, self-assured and unflappable, Lee earned plenty of criticism along the way.

“If someone living in Singapore in the 1950s could have entered a time machine and travelled to the Singapore of today, he would have found the transformations of this island literally unbelievable,” former Singapore president SR Nathan said at a September 2013 conference on the legacy of “LKY”, as he is commonly referred to.

Central to Lee’s vision were the creation of good governance, political stability, a quality infrastructure, and improved living conditions.

“Had we not differentiated Singapore in this way, it would have languished and perished as a shrinking trading centre and never become the thriving business, banking, shipping and civil aviation hub it is today,” Lee said in 2007.

Capitalism focused

To some, Lee created a capitalist alternative to Western liberal democracy, a model for countries where corruption and racial and religious divisions can be overcome by the rule of law and strict social controls. He created a hyper-efficient governing structure, and raised the standard of living and the quality of life.

“There is no question that Deng Xiaoping looked to Singapore as a principal set of lessons for China as he thought about China’s march to the market,” said Graham T Allison, director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University, and author of Lee Kuan Yew: The Grand Master’s Insights on China, the United States, and the World.

“Other states in the region have also noticed Singapore’s success. Indeed, states as far away as Kazakhstan have been attracted by Singapore’s success and have attempted to learn the lessons,” said Allison.

By empowering the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau to aggressively investigate and prosecute public and private sector crime, he created an island of non-corruption in a region that is still plagued by it.

Lee instituted a system of meritocracy in a multi-racial society to create relative harmonious relations among the Chinese, Malay, and Tamil Indian population. His belief in merit over Western thinking about affirmative action was based on his oft-stated belief that, “People are not born equal, but they must be given equal opportunity to compete under fair, transparent rules, with respected referees.”

Shooting to the top

To urban planners, Singapore is a model city. The skyline is ever-growing with glittering new skyscrapers, and streets are free of litter and graffiti. A conscious policy decision to build up with high-rises for its growing population left room enough for lush trees and green lawns seemingly everywhere, allowing the country to market itself as a “Garden City.”

The first city in the world to introduce road congestion pricing – motorists pay a premium for using busy downtown roads at peak hours – Singapore makes driving an expensive proposition, and instead lures commuters off the roads with world-class mass transit that is safe, clean, and cheap.

One of Lee’s books about Singapore’s swift rise is titled From Third World to First, and the country remains a first on many lists. It is one of the world’s richest countries, and one of the easiest places to do business, with one of the world’s highest concentration of millionaires.

It has one of the lowest crime rates in the world, the lowest rate of drug abuse, and is consistently rated one of the least corrupt countries in the world by Transparency International.

Its port is one of the world’s busiest in terms of tonnage handled, and Changi Airport is one of Asia’s most important aviation hubs. Singaporean students are among the top academic achievers in the world, and Singapore became the first Asian country to break into the top 10 national higher education systems.

On the housing front, Lee embarked on a mass home-building exercise with the construction of low-cost apartments in high-rise buildings. Today, more than 80 percent of Singaporeans live in government-built flats, with 95 percent owning their homes.

“There must be a sense of equity, that everybody owns a part of the city,” Lee said in an August 2012 interview with the Centre for Liveable Cities.

“I could see that wage-earners in Taipei and South Korea did not own their homes, they had to pay heavy rents. I aimed for a home for every family, so a large portion of their salaries need not go into paying for rents. They own it, an asset which will increase in value as the city grows.”

To become less reliant on neighbouring Malaysia for its water supply, Singapore became a pioneer in harvesting urban stormwater on a large scale for its water supply. Today, the prestigious Lee Kuan Yew Water Prize honours outstanding contributions in solving global water problems.

To protect itself in a sometimes unstable region, Singapore created a strong national defence force including a service requirement for all male Singaporeans at the age of 18.

Not all rosy

But in addition to the high rankings on so many lists, Singapore gets the lowest rankings on some lists.

Freedom House’s annual survey of political rights and civil liberties 2014 ranks Singapore as “partly free” – it is, after all, a country that famously banned chewing gum, where criminals are caned, and where homosexuality is a crime punishable by jail.

The Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index 2014 places Singapore at 150 out of a total of 180 countries – Singapore’s print and broadcast industries are licensed and regulated by the government, and the county was widely criticized in 2013 for imposing new restrictions on Internet news sites.

Lee made no apologies for his view that the media is a partner in nation-building. Lee also shrugged off criticism that Singapore’s strict social controls – criminalised activities have included failing to flush toilets, possession of pornography, and being spotted naked inside your home – go too far.

“If Singapore is a nanny state, then I am proud to have fostered one,” he wrote in From Third World to First.

Nor did he apologise for the “knuckle dusters” approach he took to fighting for his beliefs, which included suing political opponents for libel.

“I have never been over concerned or obsessed with opinion polls or popularity polls. I think a leader who is, is a weak leader,” he wrote in “The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew” (1997). “Between being loved and being feared, I have always believed Machiavelli was right. If nobody is afraid of me, I’m meaningless.”

Catherine Lim, a Singaporean author and frequent Lee critic, blogged in August 2013 that Lee amassed power by using “the two most feared instruments of intimidation and control, namely the Internal Security Act [a statute allowing detention without trial in the name of national security], and the defamation suit” to quiet political opposition.

Tommy Koh, a senior Singaporean statesman, raised the same criticism at a September 2013 conference, citing the view that the Internal Security Act was an example that Singapore had “rule by law, rather than rule of law”.

Among Lee’s political successes, the People’s Action Party – which Lee co-founded and served as first General Secretary – remains the country’s ruling party. His eldest son, Lee Hsien Loong, has served as prime minister since 2004.

The elder Lee is held in high regard by Singaporeans for his lifetime of hard work, vision, and accomplishments.

But policy analysts see Lee’s passing as an opening for a new era of leadership, ushering in an end to single-party dominance and tight social control over Singaporean life.

With the PAP losing some support in recent elections to opposition parties, Singaporeans have shown an increasing willingness to speak up, and may be ready to move beyond the government-knows-best philosophy of their rulers.

Academics such as University of Chicago political scientist Dan Slater reject the long-standing assumption that Western liberal democracy is simply ill-fitted to socially conservative societies such as Singapore.

“This argument falters because democracy does not necessarily entail less conservative policy outcomes – as the policies of many US states amply attest,” he wrote. Source: Al Jazeera