YANGON – The first phase of a tightly controlled, military-run election concluded in Myanmar over the weekend, an exercise widely dismissed by domestic critics and foreign governments as an attempt to legitimize nearly five years of army rule amid a grinding civil war.

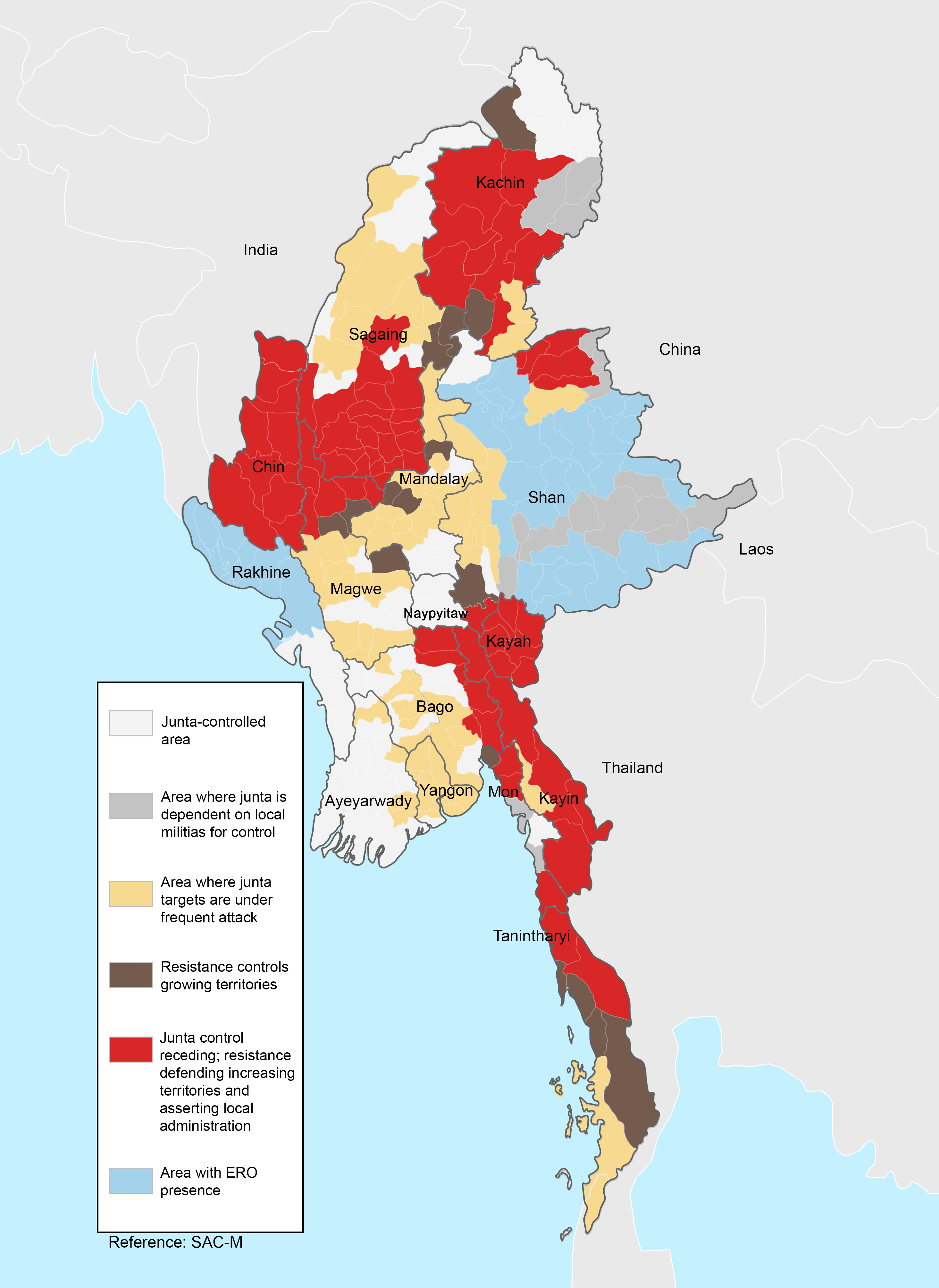

The ballot, conducted in stages through January, is taking place in only 265 of the country’s 330 townships, with large swaths deemed too unstable to vote. Independent analysts estimate that as much as half the population may ultimately be excluded. Major opposition parties have been dissolved, prominent leaders imprisoned or driven into exile, and new laws threaten severe penalties — including death sentences — for those accused of obstructing the process.

Violence Shadows the Polls

Voting on Sunday was accompanied by renewed fighting. Local officials reported explosions and air strikes in several regions, including Mandalay, where a rocket attack on an uninhabited house injured three people, according to regional authorities cited by domestic media. Near the Thai border in Myawaddy township, a series of blasts damaged more than 10 homes late Saturday night; residents said a child was killed and others wounded.

The military government rejected responsibility for civilian harm and dismissed international criticism, insisting the election is a step toward restoring stability and civilian rule.

Junta Defends Process as “Democratic”

After voting at a heavily fortified polling station in the capital, Min Aung Hlaing, the head of the junta, said the election would be “free and fair,” adding that he could not simply declare himself president. He has warned that those refusing to vote are obstructing what he called progress toward democracy.

Six parties, including the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, are fielding candidates nationwide. Another 51 parties and independents are contesting only state or regional seats, a fragmented field that analysts say favors the army’s allies.

By contrast, roughly 40 parties have been banned, among them National League for Democracy, which won landslide victories in 2015 and 2020. Its leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, remains imprisoned on charges widely condemned by human rights groups as politically motivated.

Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s Junta leader (Photo: Reuters)

International Response: Rejection and Concern

Foreign reaction over Dec. 29–30 was swift and skeptical. Western governments, including the United States and members of the European Union, reiterated that the vote lacks legitimacy without the participation of all political forces and an end to violence. United Nations officials echoed those concerns, warning that elections held amid mass displacement, censorship and armed conflict risk deepening the crisis rather than resolving it.

China, one of the junta’s most important diplomatic backers, adopted a more cautious tone, urging stability and dialogue while stopping short of endorsing the process outright. Regional neighbors in Southeast Asia, divided over how to handle Myanmar since the 2021 coup, offered muted responses, with several calling for restraint and humanitarian access.

An Uncertain Outcome

With voting scheduled to continue on Jan. 11 and Jan. 25 and results expected by the end of the month, turnout remains difficult to predict. In many townships where polls are open, entire constituencies are excluded for security reasons. Armed resistance groups have called for boycotts, and more than 200 people have already been charged under new election laws for opposing or disrupting the vote.

For many inside and outside Myanmar, the election underscores a central paradox: a promise of democracy unfolding under the shadow of war, repression and deep national division — conditions that have left the country’s political future as uncertain as ever. (zai)