BEIJING – In a test flight between Sept. 19 and 21, 2025, engineers in Hami, Xinjiang, sent aloft a helium-buoyed, tethered wind-power platform known as the S1500 — described by its backers as the world’s first megawatt-class high-altitude wind power system.

Developed jointly by Tsinghua University’s Department of Electrical Engineering, the company Linyi Yunchuan, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Aerospace Information Research Institute, the prototype is designed to harvest stronger, steadier winds above the reach of conventional towers, then send electricity down to the ground through a high-strength tether.

How the S1500 is built

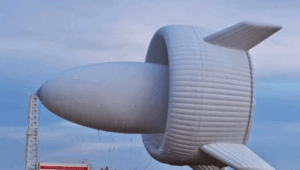

According to Tsinghua’s published project summary, the S1500 measures about 60 meters long, 40 meters wide and 40 meters high — larger than a standard basketball court in footprint — with a “main airbag” and ring-wing structure forming a ducted aerodynamic shape intended to improve stability and capture more wind.

The craft carries 12 interconnected 100-kilowatt generating units, for a rated capacity exceeding 1 megawatt, and is meant to transmit power to the ground via a lightweight tether system.

What China’s engineers say happened in Xinjiang

In the initial Xinjiang flight, the team emphasized platform and handling tests — including assembly checks, pressure-holding tests, and day-and-night operations in strong winds, meant to validate basic survivability and recovery procedures before more extensive generation demonstrations.

Chinese media coverage framed the project as a potential answer for places where building towers is difficult — deserts, islands, mining sites — and as a system that can be moved and redeployed more easily than traditional wind turbines.

How international coverage has portrayed it

Outside China, the system has been widely described as a megawatt-scale leap for “airborne wind” — and as an attempt to turn high-altitude wind into a practical power source for remote or emergency use.

Spanish coverage of the same tests highlighted the company’s stated ambition to push toward mass production in 2026and to position airborne wind as a Chinese contribution to the global clean-energy transition.

The promise — and the hard parts

Airborne wind energy has long attracted interest because winds aloft can be stronger and more consistent, potentially improving capacity factors. But scaling the concept has repeatedly run into engineering, cost and regulatory obstacles.

A U.S. Department of Energy report to Congress on airborne wind notes that commercialization depends on meeting demanding targets for reliability, autonomy and cost, and it documents how Makani — a high-profile project spun out of Alphabet’s X — ultimately shut down after struggling to secure funding for the next phase of development.

Regulators have also begun carving out rules for the airspace these machines would occupy. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration has issued an Airborne Wind Energy Systems (AWES) policy statement, a sign that tethered power devices are now on aviation authorities’ radar — literally and figuratively.

International research efforts, including work convened under IEA Wind, have similarly focused on the unglamorous but decisive questions: safety standards, operational procedures, and how to integrate a tethered, flying power plant into real-world infrastructure.

What to watch next

For the S1500, the immediate question is whether the platform can move from a successful first flight and handling trials into repeatable, grid-relevant power generation — day after day, across seasons — while proving it can be operated safely in complex weather and controlled airspace.

In other words: not just whether it can fly, but whether it can work like a utility asset. (hb)

Photo: People’s Daily